CO2 Emission targets for COP24 naturally follow on from COP21, which for real contributors was a cut of about 1% of total CO2 emissions – 356,000 tonnes of CO2 per year – until around 2025.

Given the range of global disparity in CO2 emissions, a cut of about 356,000 tonnes of CO2 per year is probably as much as can be realistically achieved in this period, at least until new ways of cutting CO2 emissions are fully implemented or even new ones invented. This could then be a CO2 emission reduction target for COP24, out to 2025.

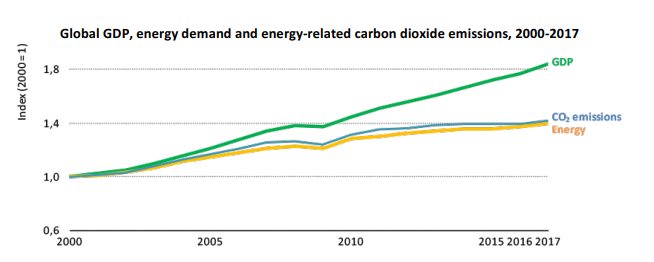

Energy-Related Emissions – Actuals

When the actual figures for total CO2 emissions come out we will know the truth about 2017, but at present we can say that energy-related emissions grew by 1.4% in 2017. However, it is noteworthy that emissions have not followed the growth in GDP.

While the USA continued the downwards march of its CO2 emissions, most of the increases in 2017 can be attributed to China (up 1.7%), European Union (up 1.5%) and the Developing Asia (up 3.1%). Developing Asia (i.e. excluding China) can be excused for its increase in CO2, since this region is well below the world average CO2 emissions per person.

COP24 – China’s emissions

Even though China’s emissions are below those of most western nations, they are well above the global average CO2 emissions. If CO2 cuts are to be achieved China cannot just stand on the sidelines and point the figure at other nations.

China cannot even say, “India’s emissions are also increasing.” The fact is that India needs to catch up on its electrification, and there is plenty of scope for it to do so. Global average emissions are around 5.0 tonnes per person per year. India’s emissions are running at less than 2.0 tonnes per year.

In regard to 2017, seasonal factors could have played a role if some emissions had “moved” from December 2016 to January 2017, (as movements in atmospheric CO2 readings seem to indicate). But the real question to be answered by China is, “What will be energy-related emissions in 2018?”

COP24 – Europe.

Europe’s failure to cut emissions in 2017 is very disappointing, particularly given the EU’s criticism of other nations (particularly USA) when the USA is actually cutting emissions.

Factors contributing to the EU’s setback include Germany’s partial loss of faith in nuclear and the dysfunctional EU ETS scheme. The question for the EU is, “What are you doing to remedy your failures?”

COP24 – Immediate CO2 Emissions target

COP21 Paris required nations to set their own targets for CO2 emission reductions. Leaving to one side China’s effective non-participation in any realistic way in the “commitment” process, it was an effective way to proceed, since non-binding commitments are likely to be more ambitious than binding commitments.

There does not appear to be any basis to change the COP21 overall target, since cuts of this magnitude will contribute significantly to the goal of decarbonising the world’s economy.

There are even ground to believe that unanticipated cuts have already been delivered. Two possibilities stand out:

- China’s well-publicized cuts in coal consumption and the move to use higher quality coal should have cut China’s emissions – but did this happen?

- A cut in India’s inefficient use of fuel for cooking and other purposes due to an increase in electrification of that nation should have given rise to a cut in net emissions – has this been factored into the IEA numbers?

COP24 – Future CO2 Emission target

Even higher rates of CO2 emission reductions are possible in the medium term. At present, the most fruitful lines of future development, not fully factored into the current targets, are:

- Increasing penetration of pumped-hydro as a way of dealing with the problem of unpredictable supply of electricity from wind-farms, without bringing in its train the “CO2 cost” of using peak electricity gas-powered generators.

- Increasing the community’s confidence in the long-term safety of nuclear-powered electricity generation, possibly via new technology currently under evaluation, leading to a higher level of take-up of nuclear energy.

- Eventual replacement of all petrol and diesel-powered passenger vehicles with electric vehicles.

If these all came to fruition, along with others not yet considered, a doubling of the annual expected CO2 emission reductions to one million tonnes of CO2 per year is not beyond practical delivery. This could be target set at COP24 for after 2025.