A 2019 IPCC report on land use recommended that people in developed nations should eat less meat. It calculated that the world’s meat intake contributes 8 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent, which represents 23% of total emissions. Most of these CO2 equivalent emissions are actually from the emission of methane by ruminant animals, like cattle, sheep and goats.

This recommendation is challenged here.

Lies about Methane emissions

The question to be asked, “Did the authors deliberately confuse the issue by using a formula to calculate CO2 equivalent emissions instead of discussing methane emissions, or was it an accident?”

Methane has an atmospheric half-life of around 9.5 years, which represents an average life of 13.5 years.

A rough guide in calculating the increase in the atmospheric level of methane is to compare the current estimated methane emissions with the estimated methane emissions 14 years ago.

An estimate of cattle/buffalo numbers in 2011 was 1,396 million, and the number in 2001 was 1,301 million. This is an increase of 95 million animals. For 2011, a detailed study indicated that methane emissions from ruminants was 107 millions tonnes.

Treating this as an appropriate guide to calculate the proportionate increase in the number of animals, this works out to be 7.3 million additional tonnes of methane, or 0.261 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent. This is only 3% of the 8 gigatonnes cited earlier.

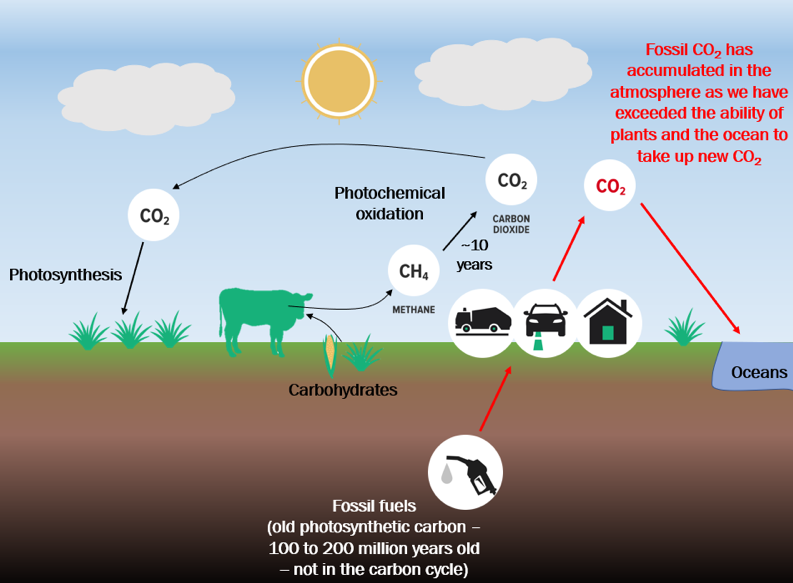

There are three factors here. Firstly, the cited report failed to take into account the fact that the half-life of methane in the atmosphere means that it doesn’t last: it mostly replaces methane already there. Secondly, methane is lost to the atmosphere by being transformed into CO2, but the effect is truly tiny (about 5/1000ths). Thirdly, in calculating the 8 gigatonnes figure, other non-methane factors were taken into account that have nothing to do with methane. Despite this, the 8 gigatonnes is clearly overstated.

Meat is not the most important factor in atmospheric methane

A recent report by Saunis, et al., calculated that the most likely break up of methane emissions in 2011 was as follows:

- 385 mt from natural sources.

- 107 mt from ruminants (cattle, sheep, etc.).

- 30 mt from rice cultivation.

- 46 mt from fugitive emissions from coal.

- 88 mt from fugitive emissions from natural gas.

- 31 mt from biomass (burning dung, etc., for cooking).

However, even this report does not explain all the historical fluctuations in the atmospheric levels of methane. Yet it is not hard to explain them: the most likely explanation is careless, but significant, additional losses of natural gas through gas leaks. The wild fluctuations in methane levels around 1990 had almost nothing to do with additional meat consumption; it was all about gas leaks. In 2011, gas leaks can be estimated to have contributed an additional 137 mt of methane in the atmosphere, with most of those emissions happening prior to 2004. Even now, I estimate that new additional emissions each year of 43 mt can be attributed to gas leaks beyond the numbers in the Saunis report.

Rather than fiddling with social engineering to cut meat consumption, cuts to methane emissions will naturally follow from the planned actions of cutting all coal mining and use, and cutting 90% of natural gas use. This will result in methane atmospheric levels reducing every year from the date that happens. A reducing level of methane in the atmosphere will happen even if red meat consumption increases in line with population.

It is not true that every pound of meat that is eaten results in a permanent increase in methane levels. It not even true that ruminants are adding to CO2 in the long-term, since the CO2 from methane actually comes from eating grass, not from underground. Today’s meat may result in higher methane levels in the atmosphere, but it is “here today” and gone in years to come. It is a part of the normal cycle.

The meat story as popularly considered and found in scholarly articles is not correct. The impact of meat on methane levels has been grossly exaggerated and the truth should begin to be told. The next UK Climate Change committee report should be revised.

2 thoughts on “Eat less meat: UN climate change report”