The aim of Net Zero GHG emissions is to stabilise global average temperatures, it is hoped that it can be achieved at 1.5C over pre-industrial levels. The calculation of CO2e for each of the GHG gases needs to take into account the impact of each of these gases upon global average temperatures. For CO2, it is quite simple: just take the quantum of the emissions themselves. 400 parts per million of CO2 equals 400 parts per million tonnes of CO2e. Since N2O has a half life of around 120 years, the normal calculation to convert to CO2e applies. In this case, 300 parts per billion of N2O equals 89 parts per million of CO2e. For the other gases a different calculation must apply. Since the other gases have a half life that significantly impacts their warming potential (methane has a half life of 9.5 years), we cannot just keep adding these warming potentials into our CO2e values. We have to take into account the progressive reduction in the atmospheric levels of these gases from previous emissions. For each year, we can (roughly) add the current emissions into CO2e, but we also have to deduct the losses into the atmosphere from previous years.

Net Zero from methane

For methane, we can simply deduct the losses attributable to the methane emissions in prior years.

- Year -1: 4.75%

- Year -2: 13.80%

- Year -3: 21.99%

- Year -4: 39.40%

- Year -5: 36.11%

- And so on into infinity.

If the world reduces the absolute value of methane emissions in each year, this gives us all a negative CO2e value that can be shared around amongst all nations. This will soften the required reductions in regard to continuing emissions of CO2 and N2O. This negative impact will continue out to 2100 if the reductions in these gases are sufficiently large. It can also go beyond this if the absolute reductions continue. For methane, the most significant element in total emissions consists of the fugitive emissions from coal extraction and natural gas extraction, transportation and use, so it is important to cut these as the first priority.

Emissions of methane are currently around 800 million tonnes. Of this total, about 26% can be attributed to coal and gas fugitive emissions (including the failure to manage leaks properly, especially around the year 1990; some mismanagement is still continuing). If coal use were entirely eliminated, natural gas cut down to only 20% of the current use (for non-energy industrial purposes only), “leaks” of natural gas cut to a “normal level”, and emissions from ruminants and rice production continued in line with population, the emissions of methane each year would be about 670 million tonnes. This reduction of 130 million tonnes of methane per year, would represent a negative CO2e, starting at zero for 2030 and growing to 3,250 million tonnes per year by 2050.

Negative CO2e from refrigerant gases

The warming potential from refrigerant gases is expected to decline from 2025, due to the further implementation of the Montreal Protocol. The atmospheric level of these gases should reduce from this date. These gases have about half the impact of methane, so let us say that it also represents a negative CO2e, starting a zero in 2025 and growing to negative 1,600 million tonnes per year year by 2050.

Positive CO2e from Nitrous Oxide

Based on the increase in atmospheric N2O, we can calculate that N2O emissions are running at about 320 million tonnes per year. It may be possible to cut emissions arising from agriculture so that the final number were 160 million tonnes per year. Based on radiative forcing at current levels of emissions, this would mean that the net CO2e from nitrous oxide would be about 1,200 million tonnes.

Positive CO2e from CO2

Based on the foregoing, for a Net Zero outcome, CO2 emissions from all sources would need to be capped at about 4,000 millions tonnes. This compares with the 35,000 million tonnes of CO2 emissions in 2018. This was made up as follows:

- Coal 13,000 tonnes (including about 2,000 tonnes of metallurgical coal and coal used for residential heating).

- Oil based fuels 9,000 tonnes.

- Natural gas 6,000 tonnes.

- Cement production 1,500 tonnes.

- Other (undefined) 5,500 tonnes.

Preferably, all coal uses would have to go if Net Zero were to be achieved. All electricity production using natural gas would have to go. All oil-based fuels need to be replaced by chemical alternatives, like ethanol or ammonia, or by electric vehicles. Alternative ways of building heating will be required, using electric air conditioning and heat pumps with local geothermal resources.

Each of these things will be a challenge, but the biggest is the complete change in electricity generation. Under Net Zero, there is no place for natural gas after 2050. At present, renewables like wind and solar cannot supply anything like baseload power, even with all types of storage, so new baseload resources will be needed, such as geothermal and modular molten-salt nuclear reactors.

Electric cars are a bit of dream, at least for nations that are not rich or have large distances to cover. For the latter, something like the ethanol-driven approach of Brazil seems to be required.

There is considerable hope for “green steel” and “green cement”. We wait in anticipation.

Carbon capture, utilisation and storage

This is a major feature of a recent report by the IEA. The question for me is whether it really will be secure at the volumes being considered. They go far beyond current storage being undertaken in depleted oil and gas wells, with the risk of subsequent leakage currently not being seriously considered.

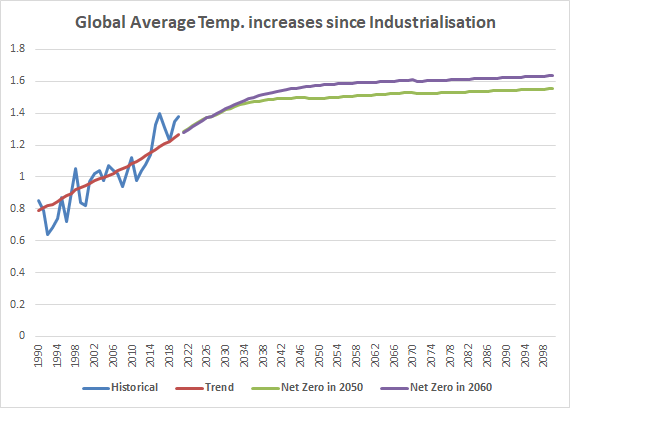

Net Zero in 2050 vs 2060

The foregoing is predicated on achieving Net Zero by 2050. Whether this is a viable strategy for all nations is debatable. A date like 2060 could be more achievable.

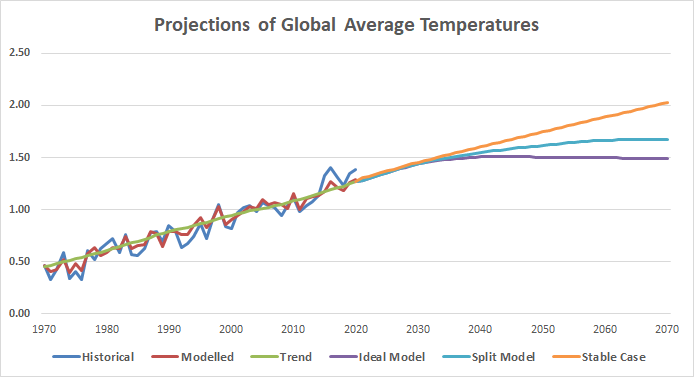

For comparison purposes, I have modelled global average temperatures out to 2070, using two targets. One is that Net Zero, according to my definition, will be achieved in 2050; the other is that Net Zero, on the same basis, is achieved in 2060.

This graph shows that a result close to 1.6C can be achieved, even if (my) Net Zero is not achieved until 2060. Of course, it will be a safer outcome if OECD nations can arrive at that point by 2050.

Conclusion

Net Zero by 2050 may be a pipe dream, but the world could give itself a number more years before we reach a stable 1.5C if urgent action were taken. This is because reduced GHG emissions in the intervening years will reduce the growth in average annual global temperatures. This will involve action on the following issues:

- Do not build any more coal-fired electricity generators where there are other options available.

- Do not use gas-fired generators for anything except for the purpose of meeting peak demand.

- Develop geothermal resources where available, and enter into fixed price contracts for the supply of electricity from such resources 24/7 (to ensure that such facilities are not bankrupted by operations that can only provide intermittent supplies.)

- Governments to push ahead with funding trials for modular molten-salt nuclear-powered electricity generators.

- Governments to immediately mandate fuel-flex vehicle electronics, so that ethanol can progressively take over as ethanol production increases and where electric vehicles are not suitable for the particular application, or are too expensive.

- Governments to mandate that ships entering their ports use non-CO2 fuels.

- Progressively implement reduced N2O agricultural practices as and when the research indicates that this is possible.

- Governments to mandate that gas not to be used for building heating in new-builds. When electric air-conditioning is not effective in cold climates, governments to mandate that heat pumps using local geothermal methods be used instead.